I’ve been reading about education as a tool of democracy and a conduit to connect learners to broader social issues. It made me think about how to learners in their world of sufficiency, could have a better and more empathic understanding of people who live in poverty.

What could a lesson look like in the classroom?

Background

$1.90 per person per day is the standard adopted by the World Bank and other international organizations to reflect the minimum consumption and income level needed to meet a person’s basic needs.

That means that people who fall under that poverty line—that’s 1/8 of the world’s population, or 767 million people—lack the ability to fulfill basic needs, whether it means eating only one bowl of rice a day or forgoing health care when it’s needed most.

The purpose of this activity is for students to raise questions and clarify their own thoughts about what things are most important to having a good life. They may also begin to see that although people living in poverty are lacking many material things, their lives may also include some aspects that the students value. This thinking will be important as students learn more about experiences of poverty.

Activity – The Good Life Road

Tell students that they will be considering what makes a good life. First, watch or read a stimulus resource as a class (such as Herbert and Harry by Pamela Allen, The Short and Incredibly Happy Life of Riley by Colin Thompson, or the TEAR video, Working Together in an Indian Village

Divide students into groups of four or five and give each group a set of cards with the following phrases on them. (They are available to print at the Global Education website ) It is helpful if each card can be printed in a different colour.

Having clean water and toilets

Having jobs for adults

Having friends and family who love and help you

Being able to make choices about what happens in your life

Having a safe place to live

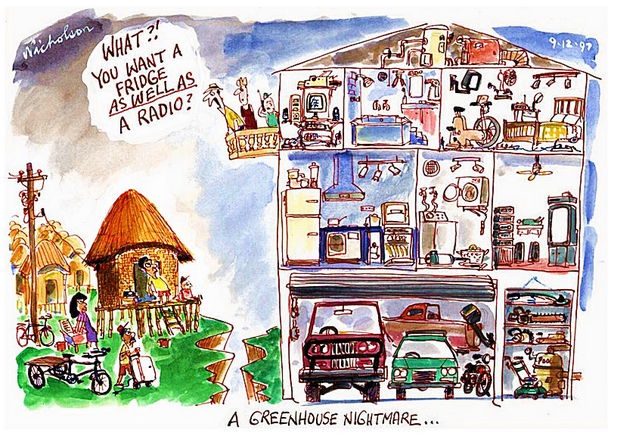

Having TVs, computers and other electronic stuff

A government that helps if you need it

Getting an education

Having lots of money

Being healthy

Having great toys

Having fashionable clothes

Being famous

In their groups, students read through the cards and make a decision about how necessary each item is for a person to have a good life. They should place each card along the Good Life Road, a line marked on the ground with ends marked ‘Very important’ and ‘Not important at all’. The cards should be positioned according to how important students think the item on the card is to having a good life. For example, if the group thinks the item on the card is vital to having a good life they should place it at the ‘Very important’ end, or if they think it is not important they should place it at the ‘Not important at all’ end. They can also place cards at any point in between

Discussion

When the groups have finished, the whole class should look at the continuum. The different coloured cards will help them to notice any trends across the cards from different groups. Students can comment on why they agree or disagree with the placement of particular items.

Is there general agreement within the class about particular items?

Are there differences between the class’s answers and what they think other people may say about a good life?

Do students’ lives actually reflect the things they say are important?

Are there any connections between the thinking in this activity and the people/characters in the book or video they viewed previously?

Do they think that people living in poverty are able to have a good life?

Can students think of anything they have in common with people living in poverty?

With thanks to the One World Centre.